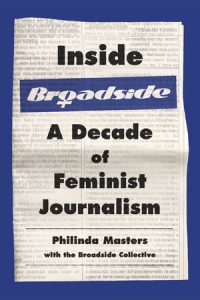

Inside Broadside: A Decade of Feminist Journalism by Philinda Masters with the Broadside Collective

Reviewed in Quill & Quire

January 2020

Publisher: Second Story Press

Two things become immediately clear upon reading Inside Broadside: A Decade of Feminist Journalism. The first is how readily women take for granted the rights and freedoms our older sisters, mothers, and grandmothers fought for. The second is how tenuous those rights and freedoms are, and how many of the battles waged 30, 40, even 100 years ago are still ongoing.

Founded in 1979 by a collective of women with backgrounds that varied from puppeteer to graphic designer to documentary filmmaker to magazine editor, Broadside was one of dozens of feminist publications that cropped up to meet the demands of women craving information and solidarity as what would ultimately be termed second-wave feminism took hold throughout the 1960s and ’70s. Published monthly by a group of volunteers who handled everything from selling advertising to typesetting and pasting up columns by hand (a feat that will be completely foreign to readers who have no recollection of life before computers), it aimed to provide a hub for women to access news, editorials, interviews, cultural analyses, and community resources. It gave space to a long list of writers, from lesser-known academics to recognizable names such as Michelle Lansberg, Eleanor Wachtel, and Margaret Atwood.

The pieces anthologized in Inside Broadside, edited by original collective member Philinda Masters (with input from current members of the Broadside collective), provide an interesting cross-section drawn from the publication’s more than 4,000 pieces. Some have aged better than others. A handful of stories about pornography, many written by collective member Susan G. Cole (who also provides the section introductions), feel oddly quaint and pearl-clutchy in light of the pornification of modern society, despite the fact that the arguments about porn’s overarching misogyny and promotion of violence against women remain true.

Reading some of these articles proves difficult largely because, in many cases, so little has changed. We’re still waiting on the universal childcare program recommended by Justice Rosalie Abella in her 1985 Royal Commission report on employment equity, for example. Most harrowing are the stories that reflect victories that are now seemingly in jeopardy. Articles lamenting the rise of conservative, far-right ideology and patriarchal control over women’s right to bodily autonomy and access to abortion are as relevant now as they were 35 years ago.

As worthy and informative as many of the pieces are (the stories about the efforts of the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women are among the best), a common criticism of second-wave feminism is that it was exclusionary, aimed at and practised predominantly by white, middle-class women whose concerns didn’t reflect those of women who fell outside those narrow parameters. Masters and Cole, who determined the final array of pieces after an initial process that involved all current collective members, are careful to include stories that call attention to this bias, but it’s impossible to read through the collection as a whole without noting the limitations the members placed on their own content.

In her sign-off editorial, published in Broadside’slast issue (Aug./Sept. 1989), Masters provides a litany of reasons for the magazine’s demise, from collective volunteer burnout to lack of financial support. But it is this statement that brings the reader up short: “The most crucial aspect of feminism in the past few years has been the efforts to incorporate anti-racist perspectives into feminist practice and analysis. White women have been forced to deal with the issues raised, forced to face the fact that it may no longer be the role of White [sic] women to frame the debate and direct the struggle. With the growth of global feminism in the past decade, White [sic] feminists are no longer the majority (if they ever were).”

A reader might well interpret this statement as an acknowledgement of the collective’s biases and an acceptance of the fact that their limited viewpoint doesn’t serve the larger feminist cause. Though one might be equally liable to take it as Masters inadvertently falling into the trap of prioritizing her own experience as a white woman over that of a woman of colour and indicating that the only way for the latter to have a voice is for the former to relinquish her own. Which side the reader comes down on will likely be determined by the reader’s own biases.

At the heart of this collection is an intention to give readers a sense of the issues that were important to the collective at the time, and to acknowledge their contribution to the feminist culture that laid the groundwork for the #MeToo movement, among other achievements. In this it largely succeeds.