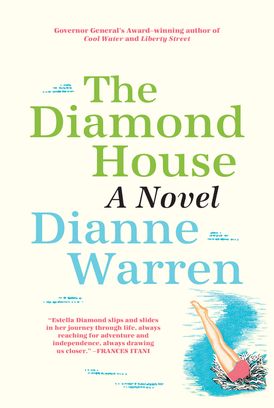

The Diamond House by Dianne Warren

Reviewed in Quill & Quire

July 2020

Publisher: HarperCollins Canada

How does one measure the worth of a life? By deeds done or money earned? The number of family and friends one holds close? Years lived? And how do these measurements differ when applied to a woman versus a man? In Saskatchewan author and playwright Dianne Warren’s latest novel, we follow the life of a woman whose path is somewhat lacking but generally ordinary. Though Warren makes it clear that in a different time or under other circumstances it could have been anything but.

When five-year-old Estella Diamond discovers that her father, Oliver, was married to a mysterious woman named Salina before he wed Estella’s mother, Beatrice, we think that Warren is setting us up for a family drama rife with intrigue and dark secrets better left unearthed. What unfolds instead is an examination of Estella’s journey from precocious child determined to inherit her father’s Regina brickworks to somewhat regretful old woman. In between, Estella fulfills the roles and duties expected of her – to an extent. A streak of rebellion and self-determination runs deep within her, inspired in part by her fantasies of Salina and how her life might have been different with a different mother.

That Estella is born in 1924 and comes of age in a time when a woman’s virtue and ability to be a “good daughter” are deeply connected to her family’s reputation and standing is a vital factor in The Diamond House. Though she is gifted with numbers, rather than going off to university Estella enrolls in the local normal school and becomes a teacher, a suitable career path for a single woman. And when she remains unmarried (despite a rather unfortunate proposal in her 30s), she is looked upon with pity by her cadre of sisters-in-law. Her brothers tolerate her, when they bother to acknowledge her at all.

What comes through most strikingly in Warren’s narrative is Estella’s frustration at her circumstances. From childhood she believes Oliver when he tells her she will inherit the brick plant. Until the day he reveals he was just humouring her and of course it will be her brothers who will take over when he eventually retires. Estella’s reward is instead the responsibility of playing nursemaid for him in his dotage. This pattern carries on throughout her life, and we ache for the wasted potential, the opportunities just out of reach. At the same time we cheer her small rebellions – taking lovers, buying a flashy car, and proving herself an astute business woman after all.

These triumphs come at a cost, of course, and it is only at the end of Estella’s life, as she contemplates the choices she has made and the price she paid to take a little of her own back that she is given the opportunity to reclaim a bit of what she’s lost. Thoroughly engaging, well written, and not remotely as dreary as it sounds, is a lovely novel that hits all the right notes.